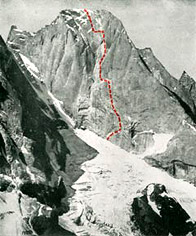

Chang Himal, North Face, Central Spur. ED+ 1800m

Man, I can’t even tell you how much sleep I’ve lost sitting in front of my computer these last few weeks, checking my emails for news from Chamonix crew sticking burly new routes on formidable faces in exotic places. And just when I think it’s safe to catch a few winks I get hit with something like this from the November 6 Alpinist Newswire:

British alpinists Nick Bullock and Andy Houseman have completed one of Nepal’s most coveted challenges: the 1500-meter north face of Chang Himal (aka Wedge Peak, 6750m) in the Kanchenjunga Himal.

The team confirmed ascent via satellite phone text. The message said the pair had returned to base camp safely on November 3.

The north face of Chang Himal was featured in “Unclimbed,” a feature in Alpinist 4 documenting the most striking unclimbed lines in the world.

A bold new line, climbed in impeccable style. Early photos of the face are stunning beautiful, alluring, dangerous – 100% Grade A climbing porn. So I brew up another pot of chai and babysit my Inbox, anxiously awaiting a report from the hardmen themselves. Like this one I just received from Andy:

In association with DMM, Mammut, Crux, Black Diamond, Mountain Equipment, Scarpa, S.I.S (Science in Sport) and the Lyon Equipment Award.

With financial support from The BMC, MEF, Nick Estcourt Award, Mark Clifford Award, Shipton/Tilman Award.

Thanks also go to Loben of Lobenexpeditions.com for a great service in dealing with all red tape, transport and base camp support, especially in supplying us with the best cook in the world (Buddy). Definitely the reason we succeeded.

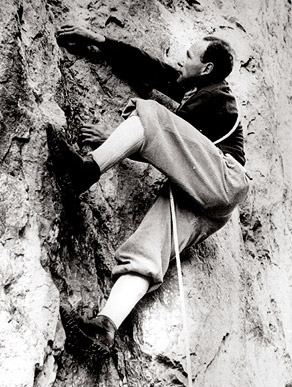

For us, the North Face of Chang Himal was an obvious though distant objective. Situated a long way from anywhere it took us a 2-day jeep ride and 10 days of walking to reach the base. The face itself is 1800 uncompromising metres of steep rock and ice that draws the eye and spurs the imagination with sweeping snow chutes, cones and ice fringes, seracs the size of semi-detached houses, bulging rotten rock, flutings and a pointy summit. Trekkers with no aspirations whatsoever sit and stare in awe. Mention that you intend to climb this face and watch their faces crack. They look and then they see you are serious. Expressions change to worry, doubt, concern. It is not that they worry about our physical health, more so our mental stability. Expressions then change once again as they realise they are stood with crazy people.

Please do not misunderstand, this face is not death. It is not the living end. It is not the best, the biggest, the highest, the boldest, not even the baddest. During an autumn where several new test routes have been climbed, here in Nepal and in China, it is certainly not the hardest. What it is, what it was, was a step into the unknown, a challenge to surpass other mountain challenges we have experienced, a step onto the largest mountain face that both Houseman and I have had the balls to walk to the base of and start climbing with just our bags packed. This is a mountain route that is not crazy, but a hard classic awaiting a few more ascents. How about it?

Here is some info for potential suitors.

Night/Day 1 – 29 October

02.30. We set out from our cave/bivvy at the base of the face and gained the large snow cone at the right of the spur via an ice/rock gully. Plunging steps into the more than favourable snow I turned to watch Houseman retching and throwing up. Hmmm, game over before it had started I thought. “Want to go down? Try again in a few days?” “Naa, I’m ok. Shouldn’t of ate that meat.” It wasn’t the meat though, it was Giardiasis [ed. – infected individuals experience an abrupt onset of abdominal cramps, explosive, watery diarrhea, vomiting, foul flatus, and fever which may last for 3–4 days], and I suspected it would get worse pretty soon. But respect to the Youth, 1800-metres to go (or to be more precise, approximately 2400 metres more to go when you add the traversing) and he was still game.

We soloed the 30° – 60° narrows on the left side, sensing the seracs above, until level with the top of the first buttress. A 70° unconsolidated slope/runnel was then followed and we eventually reached the first rock buttress. Rope out, and we climbed a 60-metre, M4+ direct line to the right of the spur followed by a further 120 metres of simul-climbing. It was now approximately 3pm, and we were at about 6000m and knackered. A fin of snow and some digging provided a reasonable step for us to recover and spend the night. Houseman was carrying a light single skin tent. Waste of time, I thought, and I was right. Never pitched it once…

Day 2 – 30 October The second rock band (make or break time).

Day 2 - Andy Houseman leaving the bivvy, starting on the 1st techy pitch of the rockband.

A rejuvenated Youth took the lead from the bivvy stating, “It looks ok.” Little do you know, I thought, as he climbed a steep runnel with sack and an unprotected bulge at the top. (M5 / 55 metres).

“Take your pick,” was the Youth’s only suggestion as I pulled the bulge and looked up at three possible overhanging continuations leading through the rock band. “None,” was my reply but eventually I took a shallow overhanging corner line sprayed with a sheen of ice. Not the best with a big bag and above 6000m. Huffing and hanging on, I pulled the exit mush with relief after 60 testing meters. M6.

Pitch 3 of the rock band included traversing right to belay beneath another vague, shallow, rotten snow runnel. (M4 / 55m).

Pitch 4 was fortunately not as steep or as rotten as Pitch 2 and went ok. (M4 / 65m).

The biggest roof on the route was traversed beneath while hunting for a bivvy site that never materialised (M4 / 70°) and in the dark a snow slope was reached on the right of the roof. (70m). A final 30 metres of 70° was climbed until back on the crest directly above the roof and at 7:00 pm a 30cm step was cut for ‘Oh what a comfy’ evening. The approximate height on the face was 6200m. (Slowed us down a tad then, that section!)

Day 2 - Nick Bullock starting up the crux pitch.

Day 3 – 31 October

The day started well with a 2.5 hour simul-climb following a broad, right-slanting, 60°-70°snow ramp to rejoin the crest beneath the final headwall where a rising traverse was taken. Oh deep joy, loads of rotten snow eventually lead to snow flutings on the right of the face. M4 / 80m. Youth took it away crossing two flutings and climbing a particularly rotten bulge of M4 rock until ensconced deep inside a fluting that gave no particular support. Well levitated, I thought as I followed. (50m). The day was finished with a flounder up the fluting with no protection and a possible dead end at 6550m. The best bivvy of the route was dug out with a fine, albeit chilly, view.

Day 4 – 1 November

A steep flounder directly out of the top of our bivvy (made easier without the weight of rucksacks which we had left at the bivvy) brightened our slightly cold and breezy day, when, with a bit of Peruvian/Nepal unprotected jiggery pokey, we entered the guts of a continuation runnel which we hoped and prayed lead to the summit crest. (70° / 180m).

And it did… A final 100 metres of 50˚ wind-scoured ice lead to the knife-edge summit at midday, directly above everything we had climbed.

After half an hour on the summit we downclimbed to our bivvy where we stopped for the evening.

Day 5 – 2 November

A tour de-force (from Youth) in constructing abseil anchors from very little indeed had us down in a one-er without too much drama. Setting off on one of the abseils, directly down the very steep rock band did have the old man puffing slightly but 13 hours later we hit and downclimbed the initial snow gully and cone and ice runnel to nestle back into our cave feeling very happy with our lot, 15 hours after leaving the high bivvy.

Game over…

The weather throughout the climb was very favourable, albeit a tad windy and slightly cool. The rock encountered on the climb was generally poor not favouring easy-to-place or easy-to-find protection for either running belays or belays. The ice was sometimes good and sometimes bad, and the snow was often rotten. All in all we had a pretty amazing time.

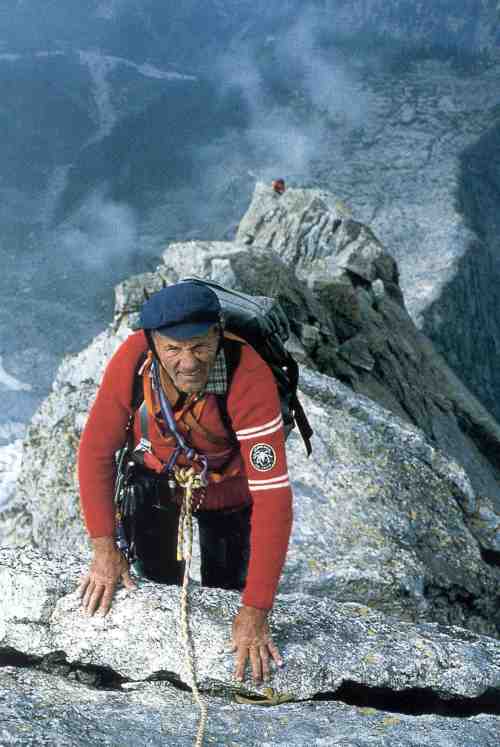

Andy Houseman, Nick Bullock - summit of Chang Himal.

Once again thanks to all of the grants, organisations, etc for the invaluable financial help, this by no-means was a cheap trip and it really would not have happened without support. Thanks again to both Andy and my sponsors, named above; including SIS and Lyon, your support is very gratefully received.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](https://i0.wp.com/img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png)